Carving with hair symbolic of memory

Back in San, Juan, the Coral Princess, dubbing itself “a small boutique hotel” adequately met our needs for the remaining two nights. I loved its palms, lavishly cascading in the yard, the tiny two-person pool, the lemony and earthy colours they’d used to give the impression of hominess and warmth. I appreciated the little Jacuzzi on the roof where I had a moment alone with my thoughts and another chance to feel the sun enriching me with the Vitamin D I lacked. Something in me had changed. I felt more alive. I had made the resolution that this trip was blessed. I had felt the presence of our ancestors throughout the journey on the islands. An inner voice was telling me that “there was more” that the trip was not over. Yes, we were back on land, in Puerto Rico, we didn’t have the pressure of returning to the ship before it potentially sailed without us, but the experiences so far had not ended. There was some kind of secret joy inside of me which I couldn’t quite share with the others. But it was agreed that we would do our ritual of libation in Puerto Rico the following morning, and I was very much looking forward to it.

There was a festive vibes on the streets of San Juan because we happened to be there on the last Sunday of the month (of November), the end of a week-long Jazz festival. We walked through the buzzing main street heading towards a supermarket to buy the gifts with which to honour the ancestors at the sea. We also sought last minute gifts, local music (some classic salsa) on our way. And we found our music – live. Bomba is a drum that plays to a dancer’s movements. There are two drums; one keeps its rhythm whilst the other precisely matches the dancer. Two elders, who had recently marked 100 years of the Bomba tradition in their family happened to be on the street and gave us a sampling of the sound. A sister took to the challenge and danced since it was a compulsion of spirit she couldn’t resist. It reminded me of a similar scene of drumming in Guyana on emancipation day.

We were up and out of the hotel by 7.30 in the morning. The beach was minutes away. Gathered in our circle of eight, we nested our gifts – fruits, sweet bread and a little bouquet of flowers on the sand. We spoke our tribute to our ancestors. We told them we remembered and will honour their humanity; we remembered their great capacity for love even when they were being cast as human cattle; they had love for each other and yet for us – even when we did not acknowledge them the way others devoutly acknowledged their ancestors. We could not be on these islands without honouring them. We remembered the ancient ones who never knew the horror of enslavement, who enriched the world with true civilisation (with art, religions of Truth, holistic education, healing traditions, science and so forth). But here on the island we particularly honoured those who endured that bitter fate and fought for their freedom and ours. We told them we would remember every one of them from all the islands – not just those we had visited – so yes we remembered One Titty Lokhay of St Maarten. We remembered our immediate and familial ancestors. We called those names we knew but in our hearts acknowledged the good ones we didn’t know but whose spirit lived with us, guiding and protecting us always.

We sang “By the rivers of Babylon” and other tunes to inspire them to manifest. We poured bottled water on the sand, white rum too. We sipped some of the rum and puffed a few smokes from a cigar - calling them. We lit incense and soon a splash of sunshine radiated on the offering, within a moment delicate drops of rain graced our expectant faces and we recognised the blessing. And so we would know and believe they were with us the most delightful rainbow arched before us like a magical arm extending toward our hearts. We vibrated in the moment, laughed and cried and marvelled, said many more thank yous to them, waved toward the sky and felt humbled at being in the powerful presence of spirit.

And this before we met Samuel Lind.

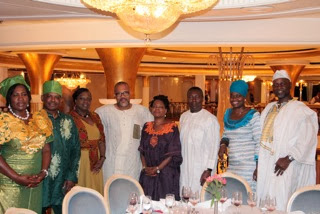

We had met our tour guide on the ship. It was no coincidence. On one of the “dress up” formal nights we wore traditional (African) clothing. Carlos asked if he could take a photo with us because he loved our dress. He was from Puerto Rico and had his own taxi service. We agreed that we would hire him on our return, since we hadn’t seen the island, and longed to visit Old San Juan.

When we called him he insisted we go to Loiza, where the most concentration of Africans lived on the island. It was a Monday morning, the town was too quiet since most people would be at work. He had hoped to take us to the Ayala family who maintain African traditions, particularly the craft of mask making on the island. We sort of wilted when we saw the house was locked up.

Across the road we had noticed a sign for – “Estudio del arte naturaleza y cultura de Samuel Lind.” A member of the Ayala family, sensing our disappointment that his family’s “museum” was closed said we should instead visit the studio.

Did that rainbow on the beach disappear? Or was it some kind of arrow shooting through time and space to lead us precisely where we needed to be?

Our first greeting into the studio was a wood carving of a sister, her long locks Samuel told us symbolised memory. Her locks were gathered into an upright pole on which her head and shoulders rested in a powerful display of conceptual symmetry. There was mystery and light emanating from every corner of the studio. Every painting and sculpture was infused with the magnificence of spirit. It seemed we were gliding through the studio, floating in the haze of an intersection between the spiritual and physical world.

This and the above image are of Bomba Dancers

Osaniyin, orisha of herbs

Samuel Lind seemed nervous as he described his creations and what had inspired him to do each piece. At first I wondered why, thinking that despite his artistic brilliance, he didn’t believe in himself. But the apparent nervousness was also excitement; he said he was glad to see us – as though our meeting was a long time coming and overdued. That other thing we were promised – that un-ended experience the spirit intuited to me the day before was now tingling my bones.

Downstairs, the studio tailed off into two smaller rooms, both greeting us with more resplendent carvings and powerful images. Samuel, born in Loiza, had created a space for the manifestation of ancestral spirits which were enshrined in the pieces. Not only ancestors but orishas like Osaniyin, the god of herbs and healing who was present in several images. It seemed natural that Osaniyin was his muse; but for me the relationship was more than this. Muse and artist were the combined force of creative expression. Samuel told us that we would recognise nature (Osaniyin) everywhere in his art. He showed us a “mock up” of an enormous carving of the Orisha that is resident in a Park on the Island.

This beautiful space colouring our senses with something enchanting was also where Samuel lived with his wife Nina. The studio was slightly off radar, in this seemingly hidden part of Puerto Rico, where Africans were marginalised. Samuel had faithfully brought life to his home town by capturing the everyday activities and cultural experiences of his people. The Bomba Dance, with which we had been treated the previous night, was featured in a number of the paintings and prints. Masks and masquerading also featured in his art; many of these images embodied the cultural mestizo of Puerto Rico. In some of the festival prints, Orishas like Legba were represented alongside Spanish conquistadors, with a Bomba drum acting as the base or root of the image. Each of these inflections was part of Samuel’s cultural experiences and therefore coalesced in his work.

Festival Print

Samuel and the proud lady in blue

Of course the space could not be complete without representations of the Taino. Bold, stunning faces, mainly of women embodying the indigenous spirits stared back at us as proudly as each African portrait. There are patchy tales about the town being ruled by a female “cacique” (a title given to indigenous chief or ruler) prior to Spanish conquest, from where it’s possible the name was derived. Puerto Rico, particularly Loiza where enslaved Africans were shipped by the Spanish has a history of “rebellion” as much as there was on any of the Caribbean islands. Forced to live together, naturally there would prevail a cultural mixing between the Taino and Africans, but also combined forces of resistance. Samuel captures this by ascribing pride to every piece. As with the African carvings and paintings of Africans, no Taino woman or child looked forlorn or sombre but exuded pride and power –light majestically radiating from them. The sculptures and paintings resonated the deep textures of culture and history – in the clothes/costumes, dances and symbolic gestures.

When he introduced us to the lady wearing a blue dress, it was impossible to resist the energy she possessed. Carlos, our guide was struck for the first time in his life by “goosepimples” – he kept asking us what the strange feeling coursing through his body meant. I can’t recall if anyone answered him because we were also feeling the energy building in us. Some of us simply embraced the feeling and cried. Others kept theirs in the confines of their heart, perhaps to release in privacy.

In a private back room we were privileged to see the wall size impression of “Terra Mujer” (mother earth). From that quieter place she could inspire the artist to produce many more magnificent pieces. The earth mother – the force of creation was powerfully represented by her son Samuel. The orishas and the ancestors anchored him and empowered his creative abilities. He told us that prior to our visit he was feeling unwell but as we embraced him for a last goodbye he said his ancestors had blessed him that day. But it was we who had been blessed all the way by the wonderful grace and love of our ancestors. I saw in Samuel an incarnated brother, I saw in the group with whom I travelled the reunion of family, which was vibrated in the exchange of our deep embrace. Hidden in the marshes of little Loiza tucked away in Puerto Rico, the spirit of ancestors remain. It was an honour to embrace them in that ritual of creativity so wonderfully expressed in the art of Samuel Lind.

Terra Mujer

Shout out

Way wive wordz provides moments of contemplation. These Warrior Shouts free the spirit from the dominance of ego consciousness. They activate intuition, breathing renewed energy into the soul force. Reactivating the soul's significance is a gateway to creativity and expansion; the eternal rhythm within everything. Introspection fulfills the soul's yearnings, connecting us to the path (or Way) of our becoming.

Tuesday, 31 December 2013

Conjuring Spirits in the Caribbean and the Art of Samuel Lind - part I

A quick glance of the islands

Outside the Ayala museum in Loiza, Puerto Rico

After a few days I justified the apparent extravagance by accepting that it was a divine gift. Although the trip – a cruise – was a year in planning it was my third for the year (after Ghana, Barbados, Guyana and Surinam). And again, I’d be going to the Caribbean. How and why – since I think things need to have some kind of spiritual purpose lest instead of alignment there is whimsical indulgence.

In any case I felt I’d been blessed already for the year with the earlier trips so I didn’t much aspire to anything and simply sauntered along with my seven companions. In truth, the only thing I hoped to do was a ritual of libation by the sea.

An unsavoury feeling must enrapture any African travelling on a ship across the Caribbean. So long as you stay inside the ship you can convince yourself you’re in an immense, luxurious hotel; one that moved without your awareness until the next morning when it arrived at a different island. You hardly feel the ship’s movements. But you cannot deny knowing of the misery your ancestors experienced in vessels less grand across those very waters. It’s as though you’re redoing the journey in a mirage of fantasy and opulence.

We set off from Puerto Rico toward Barbados. From there we would travel back, via St Lucia, Antigua, St Maarten, St Croix (US Virgin Islands) and back to San Juan (the capital of Puerto Rico). We only had a few hours on each Island before we had to get back onto the ship.

Our ship was the one of the right -"adventures of the sea"

what does this scene look like with these two docked side by side?

I loved these effervescent waves

Inside of the ship

It seemed superfluous that I should be back in Barbados since the island was featured in a recent post. Again it’s impossible to think of the island as anything other than beautiful, a darling of quietness and relaxation for tourists. Last time I was there they were discussing the introduction of fees for education; it seems the government is going ahead with this plan as the global economic crises hits the serenity of the island. Like everywhere else it’s forced to make cuts – and like its Metropolis (England), education is one of many victims.

The day we arrived in St Lucia, it was overcast, which added a rainforest feel to it. Winding roads, homes precariously built on stilts, the permanent threat of hurricanes, breath-taking views, particularly of the Piton Twin Mountains were all part of the island’s makeup. We loved it and dreamed to return for a longer stay. The mud bath in the sulphur volcano springs was joy for our skin, a high point of things to do and see there. Where they used to grow and export bananas, the island now relies solely on tourism. This would be the case for most of the islands we visited. A few of us dared to have a snake rested on our shoulders. I leapt from the mini-bus to try this curious thing I often saw people do. Though somewhat petrified, there was something liberating about the experience, and it allowed me to deal with a lifelong fear of the creatures. I have since convinced myself that my embrace of the snake was symbolic of Wata Mammi, a powerful entity within African spiritual tradition.

The Piton Mountains, St Lucia

Some were braver than others, the smiles masking fears! Or was that just mine?

Antigua had the most stunning view of the Atlantic from Shirley Heights. The rich aqua of the water seemed unreal – the image itself seemed enhanced somehow. In this area you’ll find Fort James, which was built by the British in 1706 to secure the island from mainly Spanish and French invasions. Despite this impressive view of the Atlantic the Fort had an eerie, sad feel about it. Antiguans limed at Shirley Heights on Sundays, so I imagine it would come alive differently then, and at night. Nelson’s Dockyard, though beautiful held the despicable misery of navy slaves. Concrete imported onto the island from Europe was used to build the dock, but enslaved Africans worked on it. It’s a cultural heritage site, in pristine condition, thus to better serve the prestigious annual yachting events, no doubt adored by wealthy European, particularly the British Royals. From the dock there’s an easy view of a house owned by Prince William which he inherited from his great aunty Margaret, whose partying on the island many of us might recall.

View of the Atlantic from Shirley Heights, in Antigua

We were told that there wasn’t much to see on St Maarten– that the French side was better. Here, on the Dutch side they had some lovely beaches but it was mostly fit for shopping. Previously the island was renowned for producing salt, having established the trade from its many salt ponds, but now it relied entirely on tourism. The Cruise ships, some carrying up to 6000 passengers, have their interests by the dock (tourist shops, especially jewellery). The make-ship town just outside the dock discourages cruisers from going into the actual town. We found a cute African Market (boutique) hidden among the multitude of shops in Phillipsburg; I believe it’s located on Front Street – where all kinds of retail outlets - selling clothes, jewellery and tobacco are located.

We were curious about the history and struggle of Africans on the island, since it’s one we knew little about – except that like the previous two we’d visited Africans were enslaved there; and like other islands the indigenous population had been annihilated by Europeans following Columbus imperialist adventures. And so we learnt of One Titty Lokhay, an enslaved female ancestor who would escape to Sentry Hill after committing acts against the plantation owner. She was caught and one of her breasts was removed. There’s apparently a memorial statue in her honour, which we never saw. We were grateful to Jennifer, a taxi driver and tour guide for eventually warming to us and sharing the narrative. As she did so she told us she had goosepimples. So it was that along our way we were conjuring of spirits.

All the islands were spotted with churches on every corner. This one is curiously on the shopping street in St Maarten.

St Croix was bought by the US in circa 1917 for $25 million. Before then it was owned by Denmark, though it had been fought over and owned by seven European countries – the arawaks and Caribs and then later Africans being victims of this economic barbarity. We arrived on a Saturday. Mr Ford, our taxi –driver/tour guide wanted to impress on us how quiet the island was. He took us to the airport where we saw about 10 or so passengers either coming in or leaving the island. If you’re looking for an ultra-lazy, subdued (let’s say “tranquil”) travel experience in the Caribbean (for whatever the reason), you’d find it in St Croix. In the centre we found some lovely jewellery shops but we were pleased to stumble on Riddims, selling Regga music by both local and international artists, clothes, jewellery and natural body care. The green juice and ital soursap juice we sampled from an Ital restaurant was a welcome treat from all the meaty choices on the ship.

From this quiet island we will remember the wonderful troop of iguanas that came out to greet us. There were eight of them to match our eight. The king (I’m sure it had a crown) strutted before our taxi, in the middle of the road, and paused long enough for us to take photos. The queen (as I’d like to imagine it was) was not far behind him but hung out in this little spot, again waiting and poised long enough for photos. The others were a mix of colours and sizes, at once curious looking and spectacular. I felt that these forthright, ancient creatures embodied the spirit of our ancestors.

So much more could be said about the islands – everyone heavenly. Despite the shared history of conquest especially the formulaic presence of Forts as Europeans entrenched their imperialist wings and claimed their portions of their new found gems, the islands have their own unique stories. The beauty and sunshine, the epic views of the Atlantic didn’t stifle the tangible haunting of slavery and the extermination of the original peoples of the islands. And now the people are forced to contend with a reinvigorated wanderlust called “tourism.” Still, I’m sure those smiles weren’t all phoney.

Outside the Ayala museum in Loiza, Puerto Rico

After a few days I justified the apparent extravagance by accepting that it was a divine gift. Although the trip – a cruise – was a year in planning it was my third for the year (after Ghana, Barbados, Guyana and Surinam). And again, I’d be going to the Caribbean. How and why – since I think things need to have some kind of spiritual purpose lest instead of alignment there is whimsical indulgence.

In any case I felt I’d been blessed already for the year with the earlier trips so I didn’t much aspire to anything and simply sauntered along with my seven companions. In truth, the only thing I hoped to do was a ritual of libation by the sea.

An unsavoury feeling must enrapture any African travelling on a ship across the Caribbean. So long as you stay inside the ship you can convince yourself you’re in an immense, luxurious hotel; one that moved without your awareness until the next morning when it arrived at a different island. You hardly feel the ship’s movements. But you cannot deny knowing of the misery your ancestors experienced in vessels less grand across those very waters. It’s as though you’re redoing the journey in a mirage of fantasy and opulence.

We set off from Puerto Rico toward Barbados. From there we would travel back, via St Lucia, Antigua, St Maarten, St Croix (US Virgin Islands) and back to San Juan (the capital of Puerto Rico). We only had a few hours on each Island before we had to get back onto the ship.

Our ship was the one of the right -"adventures of the sea"

what does this scene look like with these two docked side by side?

I loved these effervescent waves

Inside of the ship

It seemed superfluous that I should be back in Barbados since the island was featured in a recent post. Again it’s impossible to think of the island as anything other than beautiful, a darling of quietness and relaxation for tourists. Last time I was there they were discussing the introduction of fees for education; it seems the government is going ahead with this plan as the global economic crises hits the serenity of the island. Like everywhere else it’s forced to make cuts – and like its Metropolis (England), education is one of many victims.

The day we arrived in St Lucia, it was overcast, which added a rainforest feel to it. Winding roads, homes precariously built on stilts, the permanent threat of hurricanes, breath-taking views, particularly of the Piton Twin Mountains were all part of the island’s makeup. We loved it and dreamed to return for a longer stay. The mud bath in the sulphur volcano springs was joy for our skin, a high point of things to do and see there. Where they used to grow and export bananas, the island now relies solely on tourism. This would be the case for most of the islands we visited. A few of us dared to have a snake rested on our shoulders. I leapt from the mini-bus to try this curious thing I often saw people do. Though somewhat petrified, there was something liberating about the experience, and it allowed me to deal with a lifelong fear of the creatures. I have since convinced myself that my embrace of the snake was symbolic of Wata Mammi, a powerful entity within African spiritual tradition.

The Piton Mountains, St Lucia

Some were braver than others, the smiles masking fears! Or was that just mine?

Antigua had the most stunning view of the Atlantic from Shirley Heights. The rich aqua of the water seemed unreal – the image itself seemed enhanced somehow. In this area you’ll find Fort James, which was built by the British in 1706 to secure the island from mainly Spanish and French invasions. Despite this impressive view of the Atlantic the Fort had an eerie, sad feel about it. Antiguans limed at Shirley Heights on Sundays, so I imagine it would come alive differently then, and at night. Nelson’s Dockyard, though beautiful held the despicable misery of navy slaves. Concrete imported onto the island from Europe was used to build the dock, but enslaved Africans worked on it. It’s a cultural heritage site, in pristine condition, thus to better serve the prestigious annual yachting events, no doubt adored by wealthy European, particularly the British Royals. From the dock there’s an easy view of a house owned by Prince William which he inherited from his great aunty Margaret, whose partying on the island many of us might recall.

View of the Atlantic from Shirley Heights, in Antigua

We were told that there wasn’t much to see on St Maarten– that the French side was better. Here, on the Dutch side they had some lovely beaches but it was mostly fit for shopping. Previously the island was renowned for producing salt, having established the trade from its many salt ponds, but now it relied entirely on tourism. The Cruise ships, some carrying up to 6000 passengers, have their interests by the dock (tourist shops, especially jewellery). The make-ship town just outside the dock discourages cruisers from going into the actual town. We found a cute African Market (boutique) hidden among the multitude of shops in Phillipsburg; I believe it’s located on Front Street – where all kinds of retail outlets - selling clothes, jewellery and tobacco are located.

We were curious about the history and struggle of Africans on the island, since it’s one we knew little about – except that like the previous two we’d visited Africans were enslaved there; and like other islands the indigenous population had been annihilated by Europeans following Columbus imperialist adventures. And so we learnt of One Titty Lokhay, an enslaved female ancestor who would escape to Sentry Hill after committing acts against the plantation owner. She was caught and one of her breasts was removed. There’s apparently a memorial statue in her honour, which we never saw. We were grateful to Jennifer, a taxi driver and tour guide for eventually warming to us and sharing the narrative. As she did so she told us she had goosepimples. So it was that along our way we were conjuring of spirits.

All the islands were spotted with churches on every corner. This one is curiously on the shopping street in St Maarten.

St Croix was bought by the US in circa 1917 for $25 million. Before then it was owned by Denmark, though it had been fought over and owned by seven European countries – the arawaks and Caribs and then later Africans being victims of this economic barbarity. We arrived on a Saturday. Mr Ford, our taxi –driver/tour guide wanted to impress on us how quiet the island was. He took us to the airport where we saw about 10 or so passengers either coming in or leaving the island. If you’re looking for an ultra-lazy, subdued (let’s say “tranquil”) travel experience in the Caribbean (for whatever the reason), you’d find it in St Croix. In the centre we found some lovely jewellery shops but we were pleased to stumble on Riddims, selling Regga music by both local and international artists, clothes, jewellery and natural body care. The green juice and ital soursap juice we sampled from an Ital restaurant was a welcome treat from all the meaty choices on the ship.

From this quiet island we will remember the wonderful troop of iguanas that came out to greet us. There were eight of them to match our eight. The king (I’m sure it had a crown) strutted before our taxi, in the middle of the road, and paused long enough for us to take photos. The queen (as I’d like to imagine it was) was not far behind him but hung out in this little spot, again waiting and poised long enough for photos. The others were a mix of colours and sizes, at once curious looking and spectacular. I felt that these forthright, ancient creatures embodied the spirit of our ancestors.

So much more could be said about the islands – everyone heavenly. Despite the shared history of conquest especially the formulaic presence of Forts as Europeans entrenched their imperialist wings and claimed their portions of their new found gems, the islands have their own unique stories. The beauty and sunshine, the epic views of the Atlantic didn’t stifle the tangible haunting of slavery and the extermination of the original peoples of the islands. And now the people are forced to contend with a reinvigorated wanderlust called “tourism.” Still, I’m sure those smiles weren’t all phoney.

Tuesday, 12 November 2013

Jessica’s Rainbow: empowering the spirit

I should have known that when the tracks, particularly "Many rivers to cross" by Jimmy Cliff found their way into my Saturday night/Sunday morning - someone was travelling home. I play this to the memory of Aunty Jessica Huntley who gave so much. Clothed in brilliant white, her locks gleaming, being led by the comforting arms of her ancestors her stroll through the light will be a powerful moment of illumination. We will watch and wait for your rainbow aunty. And we'll try not to cry but always remember how you tickled us with laughter.

The above is reprinted from a facebook post I did following the news that Jessica Huntley had passed. I no longer believe in casual coincidences. If, for example, I ask the rain not to fall, then I expect a favourable response to my cosmic request. Instead of predicted rain, there will be none. Again, if I have called for a rainbow, as a sign of harmony, transformation or ascension when someone passes, I know the rainbow will appear. And it will choose a precise moment for me to observe it. We have seen many powerful tributes for Jessica and naturally we’ll see many more. I wanted to give some thoughts to the power and continuity of the spirit when it ceases to be part of the mundane but returns to its source of origin.

The aim is to understand how we can effectively remember and communicate with spirit. As Anthony Ephirim-Donkor writes when elders attain “existential perfection” they are “ensured a perpetual place in the ancestral world. They are remembered on earth when succeeding generations invoke their names socio-politically and spiritually,” (1997, p.148). The socio-political and spiritual invocation of our ancestors ensures a purposeful, effective connectivity between the physical and the spiritual worlds. This empowers successive generations to more meaningfully take up the challenge of our continued struggles. We do not have to feel weighted down by loss but ignited by the fire of the ancestral spirit and become consciously engaged in what might be called rituals of liberation.

Reverend Claudette Douglas shared a powerful tribute for Jessica at the funeral on 31st October, in which she reminded us that Africans were “god people.” Our survival has in part depended on our proper understanding of this divineness. This is not an instance or call of vanity – the head swelling notion of being identified as “gods and goddesses.” It refers to a real understanding that we can summon or halt rain - cause thunderstorms and natural calamities to disrupt the horrendous transportation of enslaved Africans across the Atlantic. Failure of technology meant that Claudette had to speak from the heart (instead of her netbook); this was not coincidental, but precise. We needed to hear her passion, feel empowered not by the words alone but the spirit of Jessica through which they came. We were all moved by her chanting of George Campbell’s poem, “History Makers” in which he acknowledges the strength and power of ordinary, hard- working women whose contributions to society are invaluable:

“Women child bearers

Pregnant frocks

Wistful toil sharers

Destiny shapers

History makers

Hammers and rocks.”

We all responded to the spiritual vibration of Claudette’s tribute which I see as a sign of our need for empowering rituals of liberation that will reconnect us to our god-centredness. It will also reunite us with those long submerged tools of resistance that are not beyond the rhetoric of politics and activism but serve to complement them.

I disregard casual coincidences because I’m convinced of the preciseness of spirit. I believe in the complementarity of physical time and spirit time. Whilst physical time has its limitations, spirit time is a divine alignment to which we must attune ourselves if we are to effectively enact our rituals, reenergise our creativity and regenerate our capacity for a sustained fight against injustice. Numbers, recurrent sequences or simultaneous experiences are part of divine order and timing that we often have little choice but to respect. And if we respect them we’ll always observe their precision and in time understand their signs – thus preparing us for the next. In this way we take nothing for granted but acknowledge and embrace the power of spirit.

On the night of the 12th October/ morning of 13th I found myself watching the movie The Harder They Come. I had linked the soundtrack with the passing of my uncle a few years ago. The lamenting, woeful tune of “Many Rivers” would tear me up emotionally. As I watched the film, the sound tracks scoring in and out, I imagined my uncle’s spirit was circling and maybe needed to be remembered. I allowed myself to drift into the memory of his passing, and felt the grief of that period. I didn’t finish the movie that night, but the next morning. When I woke up, I marked the date. This is because of an intrigue with sequences, but also I try to remember people’s birthday. I remembered that it was Herman Wallace’s birthday – posted a message to him – marking that he had been taken into transition days before. We had celebrated, amidst bitter tears, his release from the horrific Louisiana prison where under the wicked US penal system he had been detained in inhumane conditions for over 41 years, and where they had attempted to crush his spirit. I knew his funeral was on the 12th – the day before his birthday and had marvelled at that precision. But now the 13th October would have another sequential significance, not least because it was a few days before my birthday.

It was “news” you couldn’t at first believe. You replay in your mind the last conversation or communication - that email you didn’t immediately respond to. You search the imagination for what? Some sort of sign that you knew. Of course the basic signs were there – these relate to the limitations of the physical body. At 86 you accept the gracious innings –not the age alone – but the full-on, purposeful contribution of a life dedicated to the struggle for justice in all spheres. This extraordinary work/life has been well commemorated by those who knew Jessica more intimately and longer than I (Margaret Busby, Luke Daniels, Kimani Nehusi, Eusi Kwayana and many others). Once there was confirmation that the passing was real, despite recalling the last energetic laughter and sparring, I waited for the sign of spiritual precision.

The extraordinary and purposeful life of Jessica Huntley is an expression of what Anthony Ephirim-Donkor refers to as “ethical existence and generativity.” Generativity he borrows from Erik Erikson’s conceptual theories of psychological development. It refers to creativity as opposed to stagnation - of generating good experiences (actions) and altruistic contributions during the period of adulthood. These actions will guide future generations and align with the individual’s sense of responsibility to and hope for humanity. So “ethical existence and generativity” refers to the “ideal life” an individual, not only lives, but represents as their “purpose of being” (1997, pp.107-116). This “purpose of being” originates with God and accompanies the soul from that divine point of origin. A life that satisfies the soul – that is lived purposefully and in pursuit, consciously or not of “ethical existence and generativity” - attempts to effectively fulfil its divine purpose. It may be defeated physically by death – but that only applies to its earthly contribution of an extended existential goal or journey. Though the individual’s journey and “purpose of being” ends at death (in the earthly/physical plane) it continues spiritually on its return to the ancestral world. The sign I was waiting for – the rainbow - would be a symbol that the spirit is en route to be reunited with the spiritual (or ancestral) world, whilst maintaining a connection with the physical.

The rainbow appeared on the seventh day after Jessica’s transition. It had started raining early that morning and continued gently crackling against the window when I awoke. I drew the curtain slightly and noticed something beautiful about the sky. Against a mound of dark grey clouds there was an area of resplendent light and perfectly clear blue sky. I knew there had to be a rainbow so I rushed to every window in search of it. I saw it from one of the back rooms, arching over the tops of red brick homes, casting on them a momentary majesty, which my camera hasn’t properly captured. I had previously observed these rainbow signs when someone passed on my own, but this time I called Ateinda to share it with me. We declared it Jessica’s rainbow. And so it was.

We may mark the rainy weather as nothing unusual for England. We will accept that the recent storm was predictable for October; I recall a powerful one on my birthday in 1988. The lightning and thunder of Shango that we observed when a few of us were “opening to spirit” might be considered coincidental, following our invocation to Oshun at a nearby river. But I think that would be a failure of “god people” to give proper respect to the signs. For me the rains, thunders, lightning and storms have not been the casual predictions of the weather for this time of year. Even as I write this there’s a blinding light, splashing an iridescent beauty across the morning sky. Trees, looking frail with their few and waning leaves, try to resist the wind straining their branches. The sunlight bursting into the house sparks a magnificent and nurturing communion with my spirit. Now when I connect all this to the essence of Jessica, I am enacting a sort of cosmic rite that reinforces the power of spirit. Although we might be persuaded to accept the foregoing experiences of rains and thundering as nothing extraordinary, the same cannot be said for the intense bout of rains at the Nine-Night ritual.

Following the pouring of libation, there was a powerful invocation to the spirits by the drummers. The marquee in the garden held as many of us who wanted to be upfront and close to those heart-rousing beats. The drummers, led by Jessica’s son Chauncey were pounding and pounding - the singing not quite matching that force though the effort and feeling was there. The drumming was the customary calling on the Nine-Night to the spirit to return to its physical home; the drums will always invoke spirit in this way but we have to be prepared for and recognise the signs. There was no mistake that the rains which followed those drums, as though competing with their rhythms, lashing hard against the marquee signalled that the spirit was there. The drums and the communication with spirit, yielding its sign through the rains, reminded us of what “god people” are capable of. The collective energy, marking our reverence for this Queen Mother as she begins the journey of return to the ancestral realm was beautifully enacted at the Nine-Night. The rains comforted. We were all energised because everyone understood the sign. In this way we maintain continuity with the spirit. This continuity, however, should have socio-political and spiritual significance otherwise its literally mundane.

Many of the Pan-African or African centred meetings I attend open with the pouring of libation. We call the names of our ancestors, familiar and public (Yaa Asantewa, Nanny of the Maroons. Harriet Tubman, Walter Rodney, Thomas Sankhara, Kwame Nkrumah, Patrice Lumumba, Marcus Garvey, Bob Marley, Mbalia Camara, and so on). The common feature of these ancestors is their revolutionary contribution (or spirit) to our collective struggle for total liberation. Jessica Huntley will now earn her splash of water, or liquor or name drop to the ritual. But what would it really mean. Obviously, libation is our essential expression of commemorating the ancestors. Their spirit is kept alive by it, but I wonder how more effectual we can make this call to them. How can we be empowered by them to take our struggle forward, thereby building on their strength and the perpetual unity between the physical and spiritual worlds? I mean that if we only pour the libatory liquid and call their names without truly expecting some kind of effective exchange are we perhaps creating an imbalance between our world and theirs. These meetings aren’t set up with the ritual intention to ask for direction about where to strike the enemy; or for the purpose of divining a ritual (or rituals) which might assist the actual freeing of our Mumias, Hermans and others from the evil US penal system, for example. My use of the word “evil” is not candid – I mean that this system is a form of negative sorcery that destroys the well-being of individuals, community and our humanity. Historically and traditionally we have used rituals of liberation to transform this negative into positive and holistic remedies for the betterment of our communities.

If we are enacting rituals to communicate with our ancestors, especially those who lived exemplary purposeful lives in pursuit of justice, then we ought to have some measurable expectation of them. The drums at the Nine-Night we understood to be the cause for the rains. We all – collectively- accepted this. A belief in coincidences would lead us to doubt that our collective and spiritual will caused the rains – through a direct communication led by the drumming and chanting. When in that facebook post I told Jessica I will watch and wait for your rainbow that’s exactly what I did, with the confidence that it would appear. It is therefore incumbent on us to empower the spirit by calling on them to assist us in our continued fight against injustice, otherwise the force of that spirit wanes, becomes tired of being called but not expected to perform (as would be observed when someone goes into trance during a drumming session). This is the socio-political and spiritual emphasis of honouring our ancestors.

Rituals of liberation featured in the struggles of both Tousant L’Overture and Paul Bogle, the two revolutionaries that inspired the Bogle L’Ouverture Publication co-founded by Jessica and Eric Huntley. Traditional and spiritual means complemented the physical fight to yield a more formidable outcome. In the case of Bogle, Native Baptists, linking their religion to political activism, played an influential role in the 1865 Rebellion. A voodoo ceremony was used strategically for the planning of the 1791 Revolution led by Toussaint L’Ouverture in Saint Domingue. The legendary Nanny of the Maroons wielded power to fight the European enslavers by being skilled in the craft of herbs and plants, as memorialised by Lorna Goodison in her poem “Nanny:”

I was schooled in the green-giving ways

of the roots and vines

made accomplice to the healing acts

of Chainey root, fever grass & vervain

Grace Nichols also eulogised Nanny as an “Ashanti priestess/and giver of charms” someone who nurtured spirit and combined guerrilla tactics with African magic as a means of resistance (in I is a long Memoried Woman). Again, we can comfortably refute the coincidence of Jessica’s birthday, 23rd of February which is aligned with the spirit of revolution as featured in the Berbice Uprising in Guyana 1763. The sign is not simply coincidental it is precise; hence the deliberate cosmic vibration of naming their daughter Accabre after one of the progressive leaders of the rebellion; and hence Jessica’s revolutionary spirit – alighting her path to immortality.

Depiction of Nanny

Sister Cecilia’s stunning rendition of Mahalia Jackson’s “How I got over” at the funeral delighted us by the notion that the spirit would be reunited with its saviour. I’d like to think that the rainbow was the perfecting sign of Jessica’s transition, having lived an ideal and purposeful life. This is how I would answer the sombre incantation of the spirit – “falling and rising all these years, you know my soul look back and wonder, how did I make it over?”

Different cultural traditions have their own interpretations for the rainbow. In Chinese wisdom it is represented by a two headed dragon which intercedes for people by relaying thoughts and prayers from the earth bound head to the heaven bound one. In Norse mythology, the rainbow is regarded as a celestial bridge that leads the way to the ancestors or the realm of the gods. The rainbow arches – connecting heaven and earth – and thereby represents an opening or some route/crossing (either above, the bridge or below, through the arch) as a way of getting through or over (symbolic of enlightenment). So for Native Americans the rainbow is a multi-coloured serpent used by a brave young man going through initiation to ride to the spiritual world and be directed along the physical path toward illumination.

Tara, rainbow goddess in Buddhism.

Most of us identify the rainbow with the biblical story of the flood. This was a period of reconciliation, in which God promised he wouldn’t again destroy the earth so catastrophically. The rainbow was a sign of this divine promise. It is a sign of the restoration of cosmic order after storms; though I saw Jessica’s rainbow prior to our recent storm. A rainbow is not simply seen, however. To properly acknowledge it is to behold the eminence of a mesmerising moment that connects spirit and matter. For me, this was Jessica’s ladder of ascension. In Vodoun (Dahomey spiritual tradition), one of the attributes of the loa (spirit or goddess) Aida-Wedo is the rainbow. She is represented by the rainbow serpent whose scales reflect the iridescent colours of the rainbow. Aida-Wedo represents strength and integrity – that which integrates as symbolised by the many colours of the rainbow when separated from light. The serpent lives in the water –signifying the manifestation of the rainbow as the union of sunlight and water. Water is synonymous with healing, renewal and elimination. Snakes, rain and water also relate to ideas of fertility and feminine energy. The rainbow god of Ashanti also takes the form of a snake. The snake is one of the attributes of Mammy Wata, a deity rooted in the traditions of different parts of Africa which enslaved Africans took with them across the Atlantic. In some traditions, serpents are believed to represent the incarnation of deceased relatives or ancestors.

I cite these examples in my meaningful effort to interpret the sign of Jessica’s rainbow. Our traditions have bequeathed us an array of significant methods to interpret and empower the spirit and effectively enact the rituals of liberation that “god people” know. For me, the power of that mesmeric moment when we observe the rainbow is that it symbolises collectiveness and the colourful rhythm of unity. Invocations to and remembrance of spirit should not simply be mundane or half-hearted and lacklustre. Rather they should reflect a formidable complement to the physical acts and objects of commemoration by which we will continue to honour the extraordinary life of Jessica Huntley.

Depiction of a Rainbow Serpent

Mammi Water spirit,a powerful entity who must be honoured if she chooses you.

Shout Out

Some sources of interest

African Spirituality - Anthony-Ephirim-Donkor, Africa World Press, 1997

I is a Long Memoried Woman, Grace Nichols, 1993

First Poems, George Campbell, Caribbean Modern Classics, 1945

Guardian obituary by Margaret Busby: http://bit.ly/1axGjTU

Pambazuka News tribute"A great tree has fallen": http://bit.ly/1izNUEk

Creation for Liberation (1979 & 1981) YouTube video: http://bit.ly/19ax2lg

YouTube video - Jessica & Margaret: http://bit.ly/H8YVR5

Illustrated images of Jessica and Eric Huntley: Mervyn Weir

NOTE: If you would like to make a personal tribute of your experience of the Bogle L'Ouverture bookshop, or aunty Jessica please email them to me at michelleyaa@yahoo.com

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)